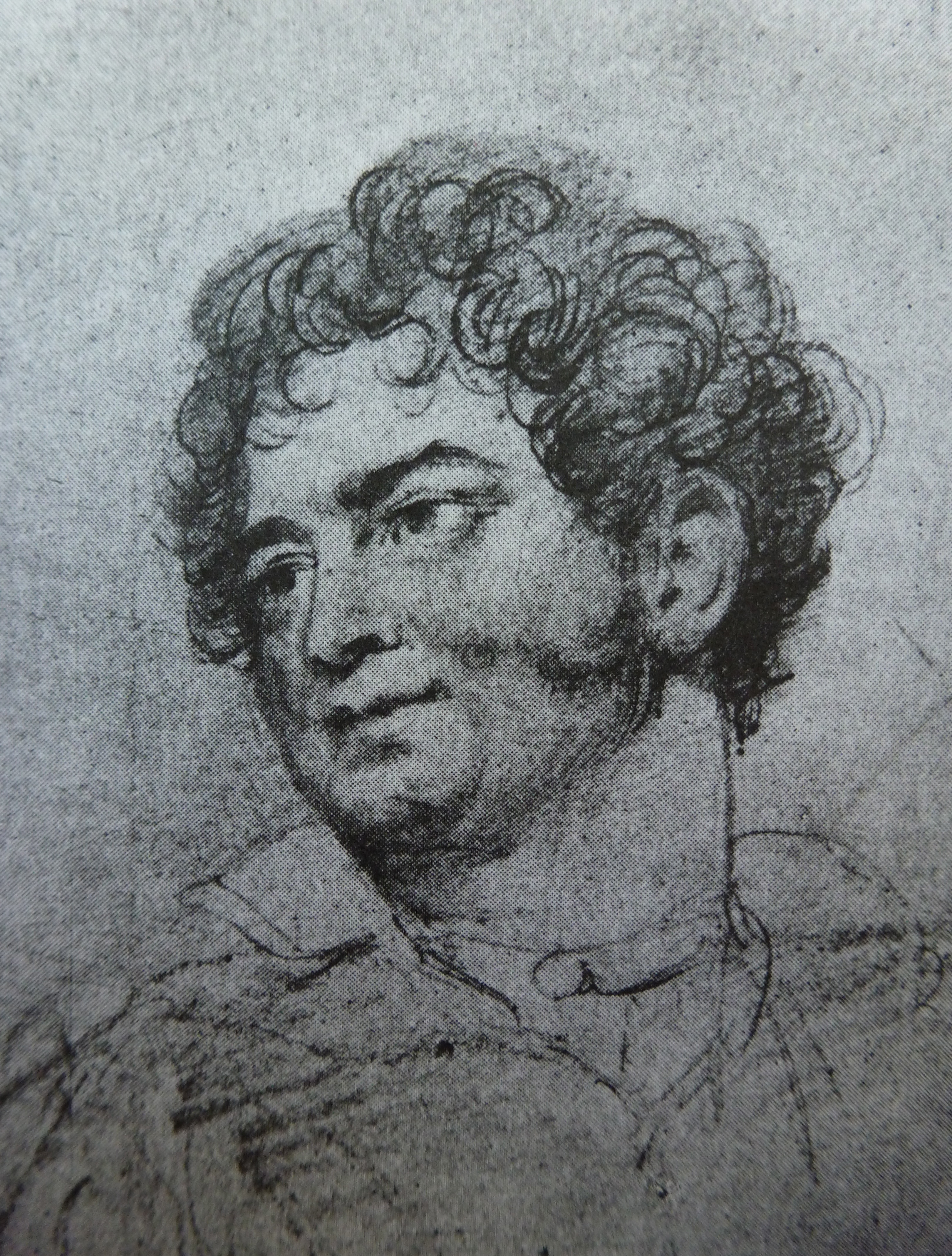

portrait courtesy of the Garcia family

born Seville, 21 January 1775; died Paris, 10 June 1832

Manuel del Pópulo Vicente García was, without any doubt, one of the most talented musicians that Spain ever produced. He was one of opera history's most celebrated tenors—the tenor for whom Rossini wrote the Barber of Seville. He was a great singing teacher. Included among his students were his own three children: Manuel Patricio Garcia (1805-1906), baritone, teacher, inventor of the laryngoscope; Maria Malibran (1808-1836), one of the most exciting prima donnas of the 1820s and 1830s; and Pauline Viardot-Garcia (1821-1910), accomplished singer, teacher and composer.

Biography:

Early Life: Seville & Cadiz (1775-1797)

García was born into a poor family (his father was a shoemaker) in Seville on 21 January 1775. There is no record that he was a choirboy in Seville's cathedral, but he probably studied with the maestro de capilla there, Antonio Ripa, as well as with the cellist and keyboardist, Juan Almarcha, who worked at the collegial church of San Salvador in Seville.

By the early 1790s García was in Cádiz where he joined the theatrical troupe of José Morales. García fell in love with Morales's daughter, Manuela, a successful singer, actress and dancer. In opposition to her parents, the young couple married secretly on 8 May 1797.

Madrid & Málaga (1798-1807)

Early in 1798 the couple moved to Madrid. On 31 May 1798 they premiered a tonadilla (a short intermezzo) composed by García, El majo y la maja. Towards the end of 1799 García got into trouble after a fight with a guard at the theater and was briefly imprisoned. After release he went to the Mediterranean city of Málaga while Manuela returned to Cádiz to sing in her father's company. This separation probably signaled the beginning of marital problems that would worsen over the next few years.

In Málaga García made a name for himself as primo tenore as well as composer. His reputation was such that he was invited to return to Madrid in 1802 where he sang the role of the Count in Mozart's Le nozze di Figaro (sung in a Spanish translation as El matrimonio de Figaro).

Over the next few years García reigned as principal tenor, composer and opera director in Madrid's theaters. He premiered several of his own operettas, most notable among them being Quien porfía mucho alcanza (1802), El criado fingido (1804) and, especially, the monologue opera, El poeta calculista (1805).The latter contained an aria, 'Yo que soy contrabandista,' which remained the most popular and influential of García's compositions. Both of his daughters sang it in recitals and interpolated it in the lesson scene of Il barbiere di Siviglia. George Sand was so enamored of the song that she wrote a play, Le contrebandier (1836), inspired by it. Franz Liszt composed a Rondeau Fantastique (1836) based on it, Robert Schumann used the text in translation in his 'Der Kontrabandiste' (1849), and, as late as 1925, Federico García Lorca featured the song in his play, Mariana Pineda.

Paris (1807-1810)

In 1807 García applied for a passport to travel to France and Italy for further study. He would never return to Spain. Part of the reason for this was that he was leaving Manuela Morales behind with two small daughters. He had taken up with the mezzo soprano and comic actress, Joaquina Briones, with whom he had performed frequently on the Madrid stage. There is no record that the marriage with Manuela Morales was ever legally terminated. To appear in Madrid in this situation would have been too scandalous, and perhaps even dangerous, legally, for García.

After initial resistance from tenors in Paris, García made his debut there in Paer's Griselda on 11 February 1808 and was well-received both by the public as well as by the critics—although the latter criticized his tendency to over-embellish. His real success came, however, with the Paris premiere of his El poeta calculista at the Odéon theater on 15 March 1809—which was cheered to the rafters.

Italy (1811-1816)

In 1811 García travelled to Italy where he perfected his singing technique under the guidance of the renowned tenor Giovanni Anzani. He made his debut at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples on 6 January 1812 in Portugallo's Oro non compra amore. In Naples he was paired with the Spanish mezzo soprano Isabel Colbran, the future wife of Gioacchino Rossini. She and Joaquina Briones (by now "Mrs. García") sang in the premiere of García's Il califfo di Bagdad at the San Carlo on 30 September 1813. This was to remain one of García's most successful operas.

After premiering Rossini's Elisabetta Regina d'Inghilterra at the San Carlo on 4 October 1815, García made history at the premiere of Il barbiere di Siviglia (at the premiere titled Almaviva, ossia L'inutile precauzione to avoid conflict with the popular Il barbiere di Siviglia by Giovanni Paisiello) in Rome on 20 February 1816.

Paris & London (1816-1825)

García returned to Paris in Cimarosa's Il matrimonio segreto on 17 October 1816. The next years would bring him his greatest triumphs, both as tenor as well as composer. It was also during this period that he opened singing schools in London and Paris and wrote his Exercises and Method for Singing (1824). Apart from Almaviva, his most famous Rossini role was as Otello, which he sang opposite Giuditta Pasta. But, strangely, the role that really took Paris by storm was García's Don Giovanni (a baritone role). By all accounts, García's interpretation was electrifying and his rendition of 'Fin ch'an dal vino' was always encored.

García's Il califfo di Bagdad was premiered in Paris on 22 May 1817 and was effusively praised by the German critic G.L.P. Sievers: "This composition shines in such a manner that it would do honour to Classical works. It is almost erudite but at the same time is in the highest degree clear and pleasing. The thematic development and the manner of the instrumentation leave nothing to be desired—even by the most serious connoisseurs." (Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung (16 July 1817), quoted in Radomski, Manuel García, p. 120)

Manuel

del Pópulo Vicente García

sketch probably done in the 1820s

formerly in the collection of Burnham W. Horner

(The Musical Times, April 1, 1905)

sketch probably done in the 1820s

formerly in the collection of Burnham W. Horner

(The Musical Times, April 1, 1905)

New York (1825-1827)

In 1825 García was invited to come to New York to direct opera at the Park Theatre. This was a momentous occasion in the history of music in the United States for these were the first truly professional performances in the country. García used the opportunity to present his young daughter, Maria, to an undiscriminating public. She quickly became the darling of New York society. While in New York she married Eugene Malibran and, although the marriage did not last, she retained his name and became established in opera history as "Madame Malibran." Apart from Il barbiere di Siviglia (premiered on 29 November 1825), García presented Rossini's Otello, Tancredi, Il turco in Italia, and La Cenerentola to the New York public. García's own L'amante astuto was premiered on 17 December 1825 as was his La figlia dell'aria on 25 April 1826. One of the most important events of the season, however, was the United States premiere of Don Giovanni on 23 May 1826 with Lorenzo Da Ponte (Mozart's librettist) in the audience.

Mexico (1827-1829)

With family tensions high after Maria's marriage on 14 March 1826 (García had been against it) García took wife Joaquina, son Manuel and daughter Pauline to Mexico in 1827 where he performed the same service as in New York: presenting high-quality performances of Rossini, Mozart's and his own works. García's Abufar ossia La famiglia araba was premiered on 13 July 1827 at the Teatro de los Gallos as was his La Semiramis on 8 May 1828. Although García had considered retiring in Mexico, the political situation was too dangerous. Amidst revolutionary zeal in the nascent republic the notorious Decree of Expulsion of Spanish citizens had been proclaimed on 20 December 1827. Although there were exceptions for those "useful in the republic" (including musicians), the situation was too dangerous and in December 1828 García, with his family, left in a convoy for the port city of Veracruz.1 En route the convoy was attacked by a band of brigands.

A letter from Vera Cruz, dated December 27th says:—"Nine coaches left there together about a fortnight since, under an escort of thirty soldiers; and although they travelled in company, each containing five or 6 passengers, well armed, they were all robbed, and lost, together, about $12,000. Among them was Signor Garcia. The rascals after completing their search, compelled him to sing several songs."According to family legend, as told by great-great-grandson Charles Garcia, his singing so impressed the robbers that they returned some of his possessions.

[Saturday Evening Post, February 7, 1829]

Paris: final years and death (1829-1832)

García sailed from Veracruz for Bordeaux on 22 January 1829. It was probably during this trip that he completed his last grand opera, El gitano por amor. In Mexico there had been protests against performances in Italian so García obligingly returned to writing Spanish operas. La Semiramis, Xaira and El gitano por amor resulted. Xaira was finished, but never performed in Mexico City. El gitano por amor was likely started in Mexico, but finished aboard ship. In any event, excerpts from it were published when García returned to Paris but the work, one of his greatest, was never performed.

García's return was anxiously awaited in Paris but in his rentrée as Almaviva at the Théâtre-Italien on 24 September 1829 his voice was heard to be in serious decline. Despite a disastrous performance as Don Giovanni on 23 December 1829 in which, unable to continue, he had to be replaced by Carlo Zuchelli, García continued to sing at the Théâtre-Italien through March of 1830. Afterwards he retired to teaching and composing, although he did continue occasionally to perform in concerts and with his students. His very last performance was in a student opera by Count Beramendi at the Tivoli Theatre on 4 August 1831.

García died after a short illness on 10 June 1832 and was buried in Paris at the cemetery of Père Lachaise (in Division 25, at the corner of Chemin Laplace and Chemin Molière et Lafontaine).

García's enduring reputation

While García's place in history as an extraordinary performer and singing teacher has been secured, his significance as a composer is still to be explored. We can only imagine what his voice must have been like from reviews and, especially, from the music he wrote for himself. We have some idea of his teaching from the writings of his students, reminiscences of his children, from his own published Exercises and from the tremendous pedagogical work of his son, who built upon the work of his father.

But the large number of García scores, in archives in France, Spain, Italy and the United States will, with time, bring to life García's music. It will take years of time-consuming work before the music can be transcribed, analyzed and tested before the public. A particular difficulty in reviving the operas is in finding singers capable of meeting the demands of García's fiendishly difficult bel canto style.

Nonetheless, a few recent experiments have been promising and have revealed the fact that García was not just another Rossini imitator, but a unique musical genius with a tremendous understanding of the voice, style and drama—all of which bodes well for a successful theatrical composer.

Both Ernesto Palacio and Teresa Berganza have released recordings of García songs and these exhibit considerable charm and sense of Spanish style.

On 7 April 2005 García's salon opera L'isola disabitata (written for his students in 1831) was premiered at Wake Forest University in North Carolina to thunderous applause. Both the drama and the music were recognized to be of sufficient quality to move a twenty-first century audience. El poeta calculista has been recorded in an excellent performance by Mark Tucker. García's Don Chisciotte was well-received at its premiere in Seville on 7 April 2007. On 3 January 2008 García's La mort du Tasse was performed in a concert version in Seville. This offered the surprise of hearing a very different "French" sound in a García composition.

With increased public interest we are certain to hear more of García's music in the future.

—James Radomski

1 In my book, Manuel García (1775-1832), p. 242, I suggested that García might have been part of a convoy of 500 Spaniards who would have left Mexico City at the end of November and were attacked by members of the 7th regiment, the very regiment that had been assigned to protect the convoy. Molly Nelson-Haber, the world's leading expert on Maria Malibran, has recently forwarded to me the above-quoted article from the Saturday Evening Post which proves that García left in a smaller convoy around the second week of December. This concurs with the recollections of García's daughter Pauline as told to her daughter, Louise, in 1908 [Louise Héritte-Viardot, Memories and Adventures, trans. from the German MS and arranged by E. S. Buchheim (London: Mills and Boon, 1913), p. 3]

Bibliography

Radomski, James. Manuel García (1775-1832): Chronicle of the Life of a bel canto Tenor at the Dawn of Romanticism, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000). Published in Spanish translation as Manuel García (1775-1832): Maestro del bel canto y compositor, (Madrid: Instituto Complutense de Ciencias Musicales, 2002).

García works published:

García, Manuel. Canciones y caprichos líricos, ed. Celsa Alonso (Madrid: Instituto Complutense de Ciencias Musicales, 1994).

García, Manuel. El majo y la maja, ed. José Subirá (Madrid: Unión Musical Española, 1973).

García, Manuel. Don Chisciotte, ed. Juan de Udaeta (Madrid: Instituto Complutense de Ciencias Musicales, 2007).

García, Manuel. L'isola disabitata, ed. Teresa Radomski and James Radomski (Middleton, Wisconsin: A-R Editions, 2006).

García, Manuel. Un avvertimento ai gelosi, ed. Teresa Radomski (Middleton, Wisconsin: A-R Editions, 2015).

Inasmuch as the publication process is interminable and I am sure many students throughout the world would be interested in seeing García works, I have decided to make my most recent transcriptions of García works available for free download:

El criado fingido

El gitano por amor

El poeta calculista

Florestan, ou Le conseil des dix

L'amante astuto (El amante astuto)

Le cinesi

L'isola disabitata

Un avvertimento ai gelosi

Los lacónicos

Salve Regina

Choruses for Racine's Athalie

Masses

This music is for personal use. All copyright restrictions apply.

If you have any questions, feel free to contact me at:

radomski@csusb.edu

—James Radomski

[Return to Homepage]